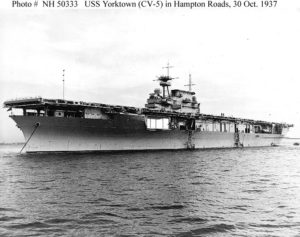

U.S.S. Yorktown (CV-5) was laid down on May 21, 1934 at the Newport News Shipbuilding company in Newport News, Virginia. Just under two years later she was launched on April 4th of  1936, sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt.

1936, sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt.

Over the next two years she was fitted out and trained in Hampton Roads, Virginia, and proceeded on her shakedown cruise in the Caribbean in early 1938. She remained on the eastern seaboard and participated in war games and fleet problems for the next year, until transferring to the Pacific in April of 1939. Once there she operated out of San Diego and continued to participate in fleet problems that helped develop carrier doctrine that was still in its infancy. In 1940 she was fitted with an RCA CXAM radar, one of the first ships to carry this new technology.

In April of 1941, as a show of U.S. naval force, Yorktown and a supporting force of cruisers and destroyers was transferred back to the Atlantic. The rising toll of the German u-boat campaign against the British caused great concern on the East Coast, and the Navy needed to be able to show it could protect American interests, even though the United States was still neutral in the conflict. American warships began escorting American flagged merchant ships, and all cruises were done on a wartime-footing, even though the Germans had strict orders not to attack American vessels. Yorktown and her escorts completed several such cruises, until she returned to Norfolk for overhaul on December 2nd, 1941.

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Yorktown immediately returned to the Pacific to reinforce the damaged fleet. She began her wartime career by escorting Marine reinforcements to American Samoa. Her charges safely delivered, U.S.S. Yorktown met up with her sister ship U.S.S. Enterprise and the two undertook one of the first offensive operations in the Pacific: The Marshalls-Gilberts Raids. Yorktown’s air group attacked targets at Jaluit, Makin and Mili. Damage was slight, both because of the air crews’ inexperience, and the fact that there was little of military importance at the locations. During the operation a Japanese “Mavis” flying boat that shadowed the task force was shot down by Yorktown’s Combat Air Patrol, the ship’s first enemy “kill”.

Following these raids, Yorktown put into Pearl briefly for replenishment and then on February 14th, 1942, headed for the Coral Sea. There she met up with the carrier U.S.S. Lexington and her escorts to patrol the South Pacific. March 10th saw a joint strike from the two carrier’s air  groups against Lae and Salamaua. Again, military targets were attacked and damaged, but nothing of significance. One result of this raid, however, was to give the air crews more practice at dive bombing and torpedo runs; experience that would be invaluable in the coming months.

groups against Lae and Salamaua. Again, military targets were attacked and damaged, but nothing of significance. One result of this raid, however, was to give the air crews more practice at dive bombing and torpedo runs; experience that would be invaluable in the coming months.

Lexington returned to Pearl Harbor for a refit and Yorktown stayed in the Coral Sea for extended patrols. She continued to do so with only a minor visit to Tongatabu in the Tonga Islands, until the Lexington returned. Once rejoined the two carriers headed back to the Coral Sea. There they joined in battle with the Japanese in The Battle of the Coral Sea, May 4th through 8th, 1942. The battle, a result of an attempt by the Japanese to invade Port Moresby, New Guinea and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands, saw the Japanese invasion turned back in the first ever carrier battle, and the first naval battle in history where the opposing ships never sighted one another. The Japanese lost the light carrier Shoho, while the Americans lost the heavy carrier Lexington. Yorktown also sustained damage that many said would take months of shipyard work to repair.

Those months in the shipyard would not come, however, as Yorktown returned immediately to Pearl Harbor to prepare for another battle. U.S. Naval Intelligence had broken a top Japanese code and knew that the enemy’s next move would be to invade Midway Island, at the very northwestern tip of the Hawaiian island chain.

Yorktown entered Pearl Harbor on May 27th, and just three days later, patched up from a hurried dry dock visit, got underway towards Midway. Her repairs were nowhere near sufficient, but they would have to do. Yorktown rendezvoused with her sisters Enterprise and Hornet at Point Luck, northeast of Midway, and lay in wait for the Japanese.

Search planes from Midway detected the Japanese invasion force and the separate Japanese carrier battle group early on June 4th. Yorktown had the search duty that day, and stayed on station to recover her search aircraft while Enterprise and Hornet raced west to launch their strikes. Once Yorktown had recovered her aircraft, she followed and launched her own strike. This separated the two task forces, and would have dramatic consequences for Yorktown. Due to errors in plotting and aircraft getting lost, Enterprise and Yorktown’s dive bombers arrived over the Japanese carriers at the same time (all three carriers torpedo plane squadrons had been turned back with atrocious losses already, and Hornet’s dive bombers got lost and missed the action entirely). Within the space of minutes, the SBD Dauntless aircraft had turned three Japanese carriers into burning wrecks.

Of the Japanese carriers, only the fourth, Hiryu, had escaped the initial inferno. She subsequently launched a strike of 18 Val dive bombers and 6 Zero fighters, which found Yorktown just after 1400 hours. Three bombs struck Yorktown and knocked out all power. It took over an hour for the engineers to get the engines and boilers back online and functioning. With power restored, Yorktown began making headway again, just as another attack appeared on the radar screen at 15:50.

Of the Japanese carriers, only the fourth, Hiryu, had escaped the initial inferno. She subsequently launched a strike of 18 Val dive bombers and 6 Zero fighters, which found Yorktown just after 1400 hours. Three bombs struck Yorktown and knocked out all power. It took over an hour for the engineers to get the engines and boilers back online and functioning. With power restored, Yorktown began making headway again, just as another attack appeared on the radar screen at 15:50.

Yorktown immediately began to churn up to her now top speed of 20 knots, and launched what few fighters she had aboard, some with so little fuel in them that they were prepared to fight and ditch in the water. The Japanese strike, also from the sole surviving Hiryu, of Kate torpedo planes, pressed their attack and Yorktown, unable to dodge them due to her reduced speed and damaged state, took two torpedoes in her port side.

The ship took on an immediate list and lost all power. Captain Buckmaster passed the order to abandon ship once the list passed 26 degrees. With all of the crew off and the battle proceeding on without her (aircraft from the Enterprise, including many Yorktown orphans, found and destroyed the Hiryu), the Yorktown clung to life. After a full night of refusing to sink, a salvage party was assembled and returned to the carrier. Salvage and towing was well underway when, on June 6th, the Japanese submarine I-168 slipped through the escorting destroyer screen and fired a spread of torpedoes at Yorktown. The destroyer Hammann, tied alongside Yorktown to provide power, was struck by one torpedo and split in half, sinking in a matter of minutes. Two  other torpedoes struck Yorktown. The carrier was again abandoned, and the hope was to board her and continue the salvage the next day, but dawn of June 7th saw Yorktown slowly settling and rolling over. Shortly after 0700 hours U.S.S. Yorktown rolled onto her port side, capsized, and sank.

other torpedoes struck Yorktown. The carrier was again abandoned, and the hope was to board her and continue the salvage the next day, but dawn of June 7th saw Yorktown slowly settling and rolling over. Shortly after 0700 hours U.S.S. Yorktown rolled onto her port side, capsized, and sank.

With most ships, a wartime sinking is the end of their story. Not so with U.S.S. Yorktown. In May of 1998, Dr. Robert Ballard, of Titanic discovery fame, found her wreck 3 miles below the surface of the Pacific. She rests upright on the ocean floor in remarkably good condition. Part of her aft flight deck has broken off, possibly due to the impact when she struck bottom, but otherwise she is in excellent shape, mostly due to the lack of marine life at that depth.